As the affordable housing crisis has deepened, many state and local governments have started to address the need for affordable housing, in part through inclusionary housing programs. Inclusionary housing programs provide developers of residential housing certain benefits for including affordable units in new, primarily market-rate rental properties. However, not all inclusionary housing programs are created equal. Some permit the share of units that are set aside as affordable to be as low as just 5%. The most effective programs tend to set aside at least 20% of the new units to be affordable to lower-income tenants in exchange for benefits that help offset the cost of new construction.

What Incentives are Offered?

Benefits offered to developers can include waivers of zoning requirements, including density, area, height, open spaces, and use. They can also include an expedited permitting process, fee waivers, or reduced parking requirements per unit. These programs also frequently provide a tax abatement lasting several years. Since inclusionary housing programs do not require direct subsidy dollars to create affordable housing, they are considered a market-based solution for affordable housing, making these programs attractive to cash-strapped municipalities.

Seattle’s Tax Abatement

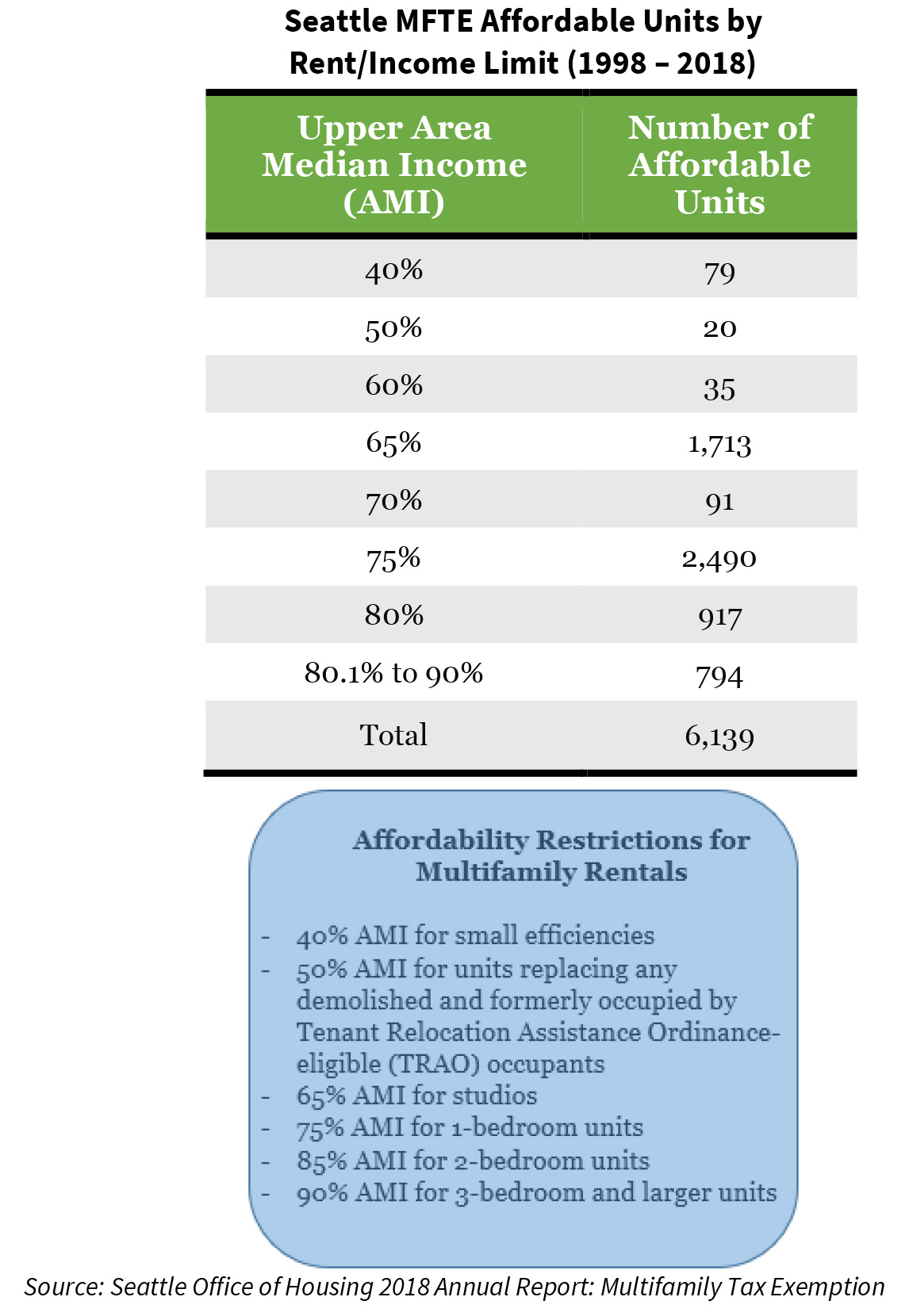

Seattle’s current Multifamily Property Tax Exemption (MFTE) Program has been successful in producing new affordable units. As shown in the adjacent table, it has produced over 6,1oo new affordable apartments and almost 33,000 total new units over the past 20 years.

The MFTE Program is available as an incentive program in all areas of Seattle zoned for multifamily. It provides up to a 12-year tax exemption on new multifamily buildings in exchange for setting aside between 20% and 25% of a project’s units as income and rent-restricted for 10 years. As shown in the lower insert, income restrictions vary depending on unit size.

Affordable Rental Units for Families

Not only is there a shortage of affordable multifamily units, but many new multifamily units are generally not ideal for families. Seattle attempts to incentivize the development of larger apartments by reducing the share of affordable units in exchange for more bedrooms.

Under the MFTE, at least 25% of units are required to be affordable at the limits shown in the adjacent insert, unless a minimum number of two-bedroom or larger units are provided. In this case, the MFTE affordable set-aside is reduced to 20%. Even so, just 792 two-bedroom units, 11 three-bedroom units, and 4 four-bedroom units had been developed through 2018, the last year for which data is available.

Seattle’s Tax Abatement Up for Renewal

Seattle’s MFTE program was recently renewed through 2022. According to the mayor’s office, the MFTE would support at least 1,300 new affordable units over the next three years. Also, the new legislation limits rent increases to no more than 4.5% annually on affordable units. Rent and income limits would still be tied to the Area Median Income that are published annually by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, as in the past. The legislation also provides that rents will not decrease if income levels decline.

Austin’s Affordability Unlocked

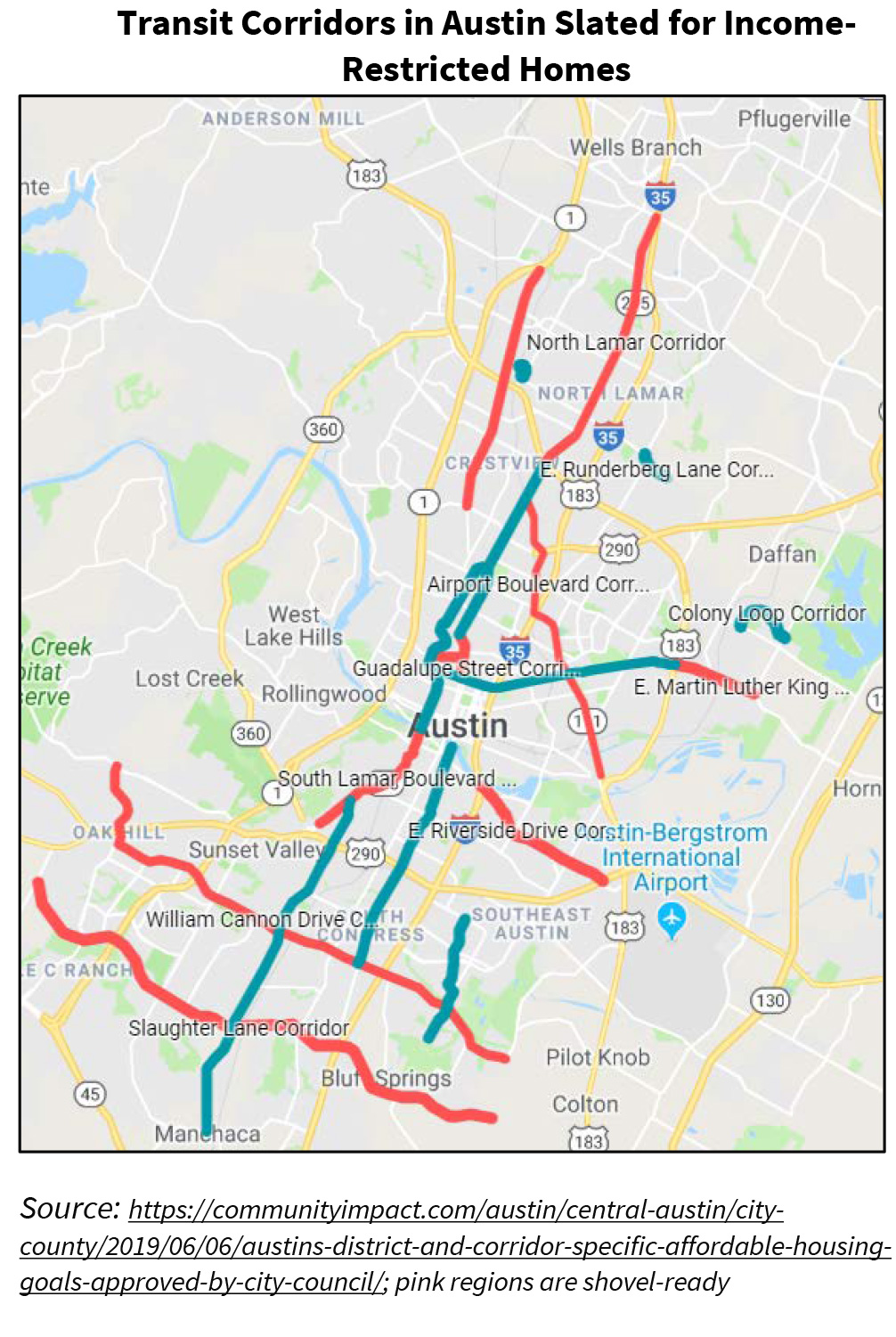

Austin’s most recent inclusionary housing program, which was passed this year, combines density and deep affordability. The “Affordability Unlocked” Development Bonus Program seeks to capitalize on the $250 million in Affordable Housing Bonds that voters approved in 2018. It does so by enabling developers to include more affordable units in their developments and to increase density along the transit corridors shown on the adjacent map. The program is expected to help the city meet its goal of building 60,000 affordable housing units by 2027.

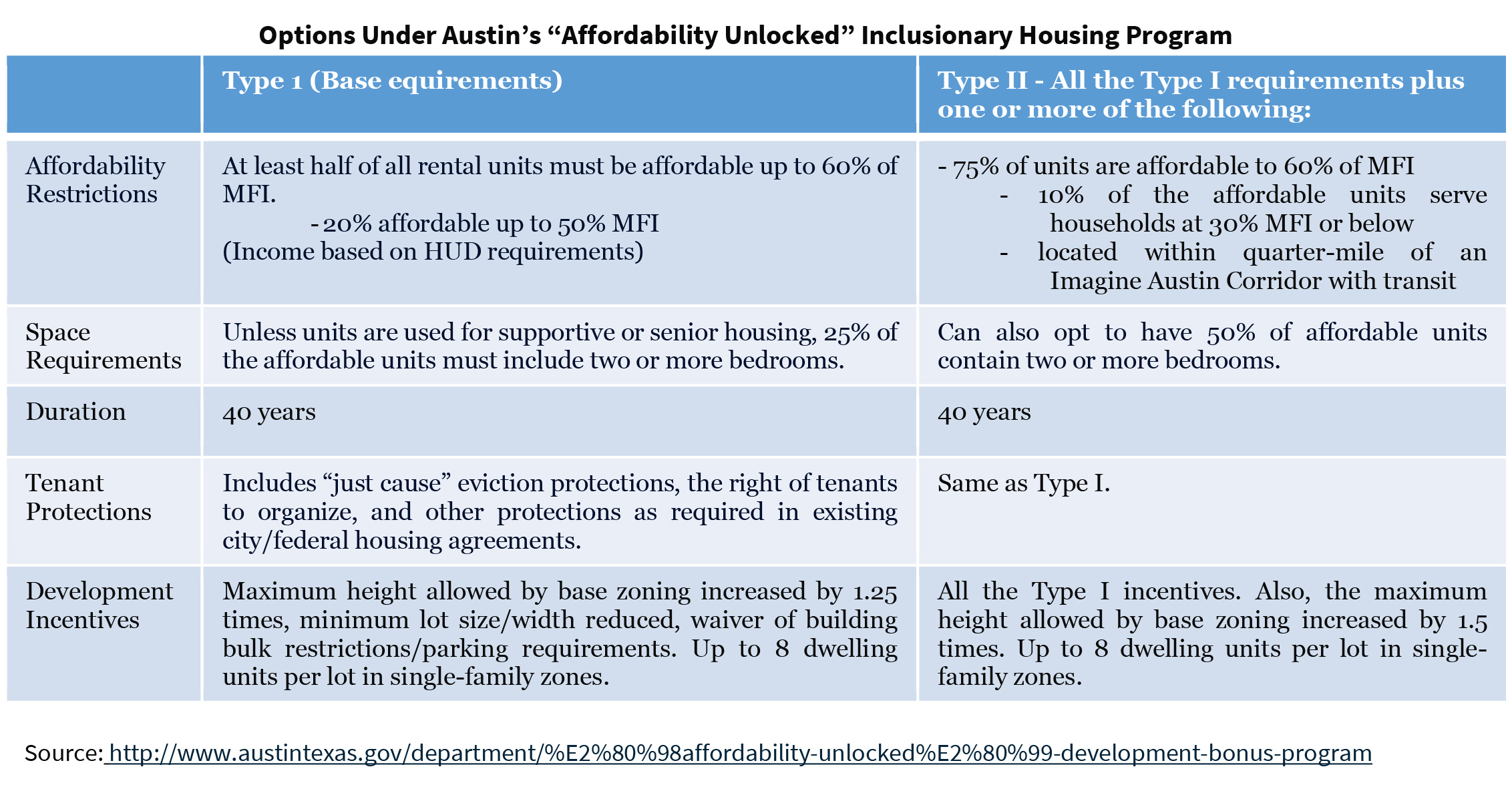

A Plan for Deep Affordability

The program applies city-wide to any single-family or commercial lot. It allows at least six housing units on any feasible lot by waiving certain density, setback, height, and parking spot regulations. As shown in the table below, at least half of a development’s units must be affordable to households with incomes up to 60% of the median family income (MFI), with a portion of those serving households up to 50% of MFI. These units are rent-restricted. In exchange, the program offers extensive waivers and modifications of development regulations, thereby allowing for more apartments. Developers offering between 75% or more of a property’s units as affordable, as well as reserving 10% of the units for residents earning 30% of MFI, or locating a property within a quarter-mile of a transit corridor can achieve an even greater density bonus.

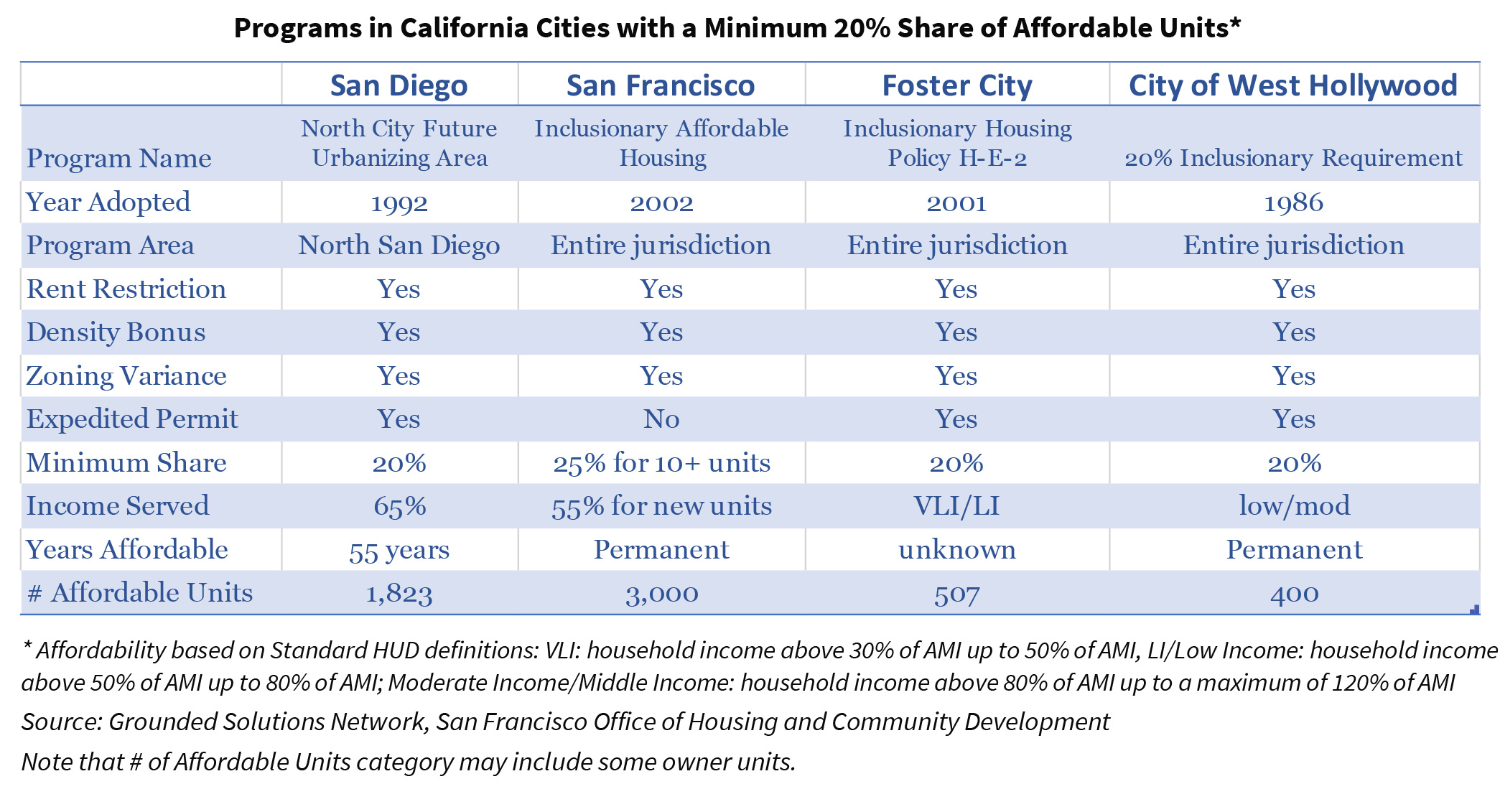

California Has Several Programs with 20% Set-Asides

In order to incentivize the development of affordable housing, California has a state-wide density bonus requirement. Local jurisdictions can provide a 35% density bonus for developers who set aside least 20% of apartments in a new property to be affordable to low-income households earning up to 80% of area median income (AMI). Yet set-aside shares remain at less than 20% for affordable rentals in most programs in major California cities.

San Diego’s North City Future Urbanizing Area program, which applies to the northern part of the city, requires housing developers to dedicate 20% of new units to renters earning no more than 65% of AMI. Units are required to remain affordable for 55 years. In exchange, developers are given density bonuses and other zoning variances, as well as expedited permitting. The program has produced more than 1,800 rent-restricted units to date.

West Hollywood has a similar program that requires 20% of residential projects with 10 or more units to be reserved for lower-income and moderate-income households. Inclusionary units must be rent-restricted, dispersed throughout the building, and include the same finishes and appliances as the project’s other units.

San Francisco's inclusionary Housing Program requires developers of projects with 10 or more units to pay an Affordable Housing Fee, or to rent a share of the units at a below market-rate level that is affordable to low- or middle-income households. For residential units developed on or after January 12, 2016, in projects of at least 25 units, 25% of new units must be affordable. However, developers may choose to fulfill this requirement offsite.

No Impact on Inclusionary Housing from New Rent Control

In October of this year, California enacted the Tenant Protection Act of 2019, which limits rent increases for many properties with rental units throughout the state of California. One concern with any rent control law is whether new supply will be affected. That’s because it is expensive to build new apartments, and curtailing rent growth on all of the new units in a new market rate development generally makes it difficult for developers to recoup costs. However, there are a couple of provisions that should prevent any curtailment in new apartments being delivered in California, including those developed under inclusionary housing programs. Under the new rent law, the new rent increase cap applies only to older, existing properties on a rolling 15-year basis. Therefore, a new multifamily rental property built in 2020 will not have all of its units be subject to rent control until 2035.

Boulder, Colorado: Shifting to Rentals

Boulder’s inclusionary housing program was created in 2000 but started targeting renters in 2008. It was updated in 2018 to include housing targeted to middle-income households earning between 80% and 120% of AMI. However, a significant set-aside remains for more affordable rental units for low income renters earning less than 80% of AMI.

Any development containing five or more dwelling units is required to include at least 25% of the total number of units as permanently affordable, with at least 20% of the units affordable to low- or moderate-income households. Another 5% of the required affordable units must be affordable to middle-income households. In addition, the inclusionary housing ordinance authorizes the city manager to use rule-making authority to annually adjust percentages, to help further incentivize additional on-site affordable units. Since inception, more than 2,800 low- and moderate-income affordable rentals have been built.

NYC 421-a Tax Exemption Program Prolific...

Under New York City’s 421-a tax exemption program, property owners are exempt from paying additional real estate taxes on the increased value of an apartment building once construction has been completed. In exchange, developers set aside a certain percentage of units to be affordable. These units enter the rent stabilization program, which has generally limited rent increases to between zero and 1.5% annually over the past five years.

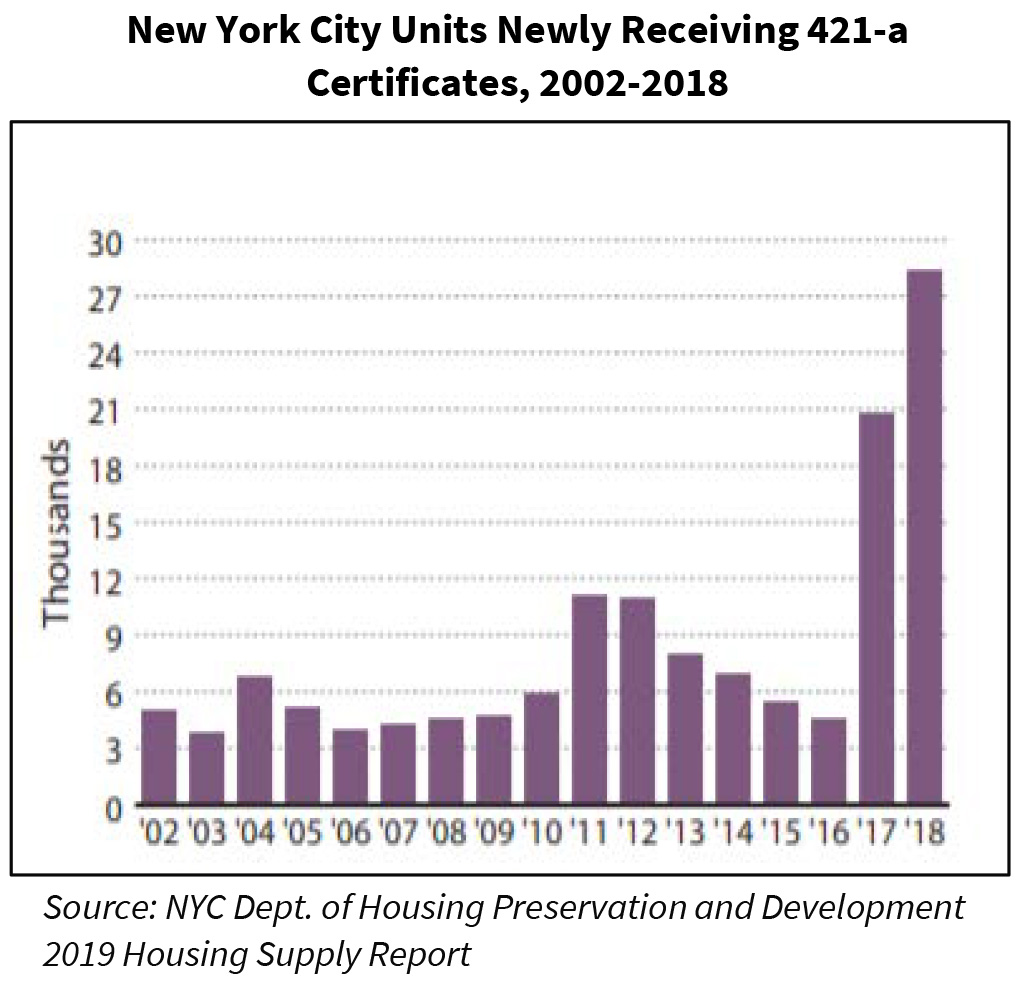

In 2017, the 421-a program was updated through the Affordable New York program and the length of tax abatement increased from a maximum of 25 years to a maximum of 40 years. As seen in the chart to the right, with the greater incentive, the number of units issued a 421-a tax exemption certificate jumped by over 300%. As a result, the number of new affordable rent-stabilized units increased dramatically. Further, the 2019 Housing Supply Report issued by the New York City Rent Guidelines Board estimates that 116,000 rent-stabilized units will benefit from 421-a tax exemptions and abatements this year alone.

Massachusetts: 20% Set Aside for Affordable Units

In addition to metro areas, some states offer voluntary, state-wide programs. For example, Massachusetts’ Chapter 40B program has been quite successful in enabling local zoning boards to approve affordable housing developments under flexible rules, in exchange for long-term affordability restrictions. Also known as the Comprehensive Permit Law, Chapter 40B was enacted in 1969 with the goal of ensuring that 10% of housing in each community is affordable to lower-income residents. Of these, at least one quarter of rental units must be affordable to lower-income residents earning up to 80% of AMI. Alternatively, the project can ensure that 20% of rental units are affordable to households earning up to 50% of AMI.

As of 2016, the Chapter 40B program has created about 48,800 units of multifamily rental housing. An estimated 29,800 units, about 61%, are income restricted. Some of the units were also subsidized with Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC).

Connecticut: 30% Minimum Set Aside

Connecticut also has a statewide program. Under its 8-30G statute, in communities where less than 10% of housing is affordable, developers may receive automatic approval for projects when 30% of the new units are deed-restricted for a minimum of 40 years.

Fannie Mae Finances Multifamily Properties Participating in Inclusionary Housing

Fannie Mae’s Special Public Purpose lending product finances properties with third-party deed restrictions that fall outside of the LIHTC and Project-based Section 8 programs. These include properties that add new affordable supply.

For example, in 2018, Fannie Mae provided $37 million of permanent financing on 188 new multifamily rental units in the East Main Apartments property located in Norton, MA, which was constructed under the state’s 40B program. Construction was completed in 2017 with 47 new units earmarked for low-income renters.

In 2019, Fannie Mae also provided $9.6 million of permanent financing for the 28 units in The Stack in New York City, which was constructed using streamlined modular construction and completed in just 10 months. The property’s owner obtained a 25-year tax exemption under the city’s 421-a program, requiring that 20% of the units (six units) had to be restricted as affordable to tenants earning 60% of AMI. In addition, the affordable units were rent restricted.

Programs with Offsetting Support Tend to be More Successful

Adopting an inclusionary housing program in and of itself is not enough to guarantee that new affordable multifamily units will be added to the metro’s housing stock, even with a greater share of units set aside to be affordable.

According to the National Housing Conference Affordable Housing Policy Review Journal publication, Inclusionary Zoning: The California Experience, developer opposition and land shortages are among the factors that can slow down the production of all types of new housing, not just affordable housing. The study also notes that the most productive programs were much more likely than other programs to subsidize the construction of affordable units. As a result, pairing inclusionary housing with secondary sources of funding from state and local governments is most likely to generate a more generous amount of new affordable units.

Tanya Zahalak

Senior Multifamily Economist

Multifamily Economics and Market Research

December 2019

Opinions, analyses, estimates, forecasts, and other views of Fannie Mae’s Multifamily Economics and Market Research Group (MRG) included in these materials should not be construed as indicating Fannie Mae’s business prospects or expected results, are based on a number of assumptions, and are subject to change without notice. How this information affects Fannie Mae will depend on many factors. Although the MRG bases its opinions, analyses, estimates, forecasts, and other views on information it considers reliable, it does not guarantee that the information provided in these materials is accurate, current, or suitable for any particular purpose. Changes in the assumptions or the information underlying these views could produce materially different results. The analyses, opinions, estimates, forecasts, and other views published by the MRG represent the views of that group as of the date indicated and do not necessarily represent the views of Fannie Mae or its management.